Silk threads undergo a meticulously planned creation process, utilizing natural sources from silkworms, typically the mulberry silkworms (Bombyx mori).

The process initiates with the gathering of silkworm cocoons, each unfurling to form a span that can extend up to 1,500 meters. Subsequently, the collected cocoons undergo boiling or steaming to soften the sericin, the protein binding silk fibers together. This softening stage facilitates the unwinding of silk threads.

Once softened, the cocoons are unwound, often employing a device known as a “winding machine.” As the cocoons unravel, extended silk fibers are wound onto spools. These unwound silk fibers are then twisted to create highly durable threads.

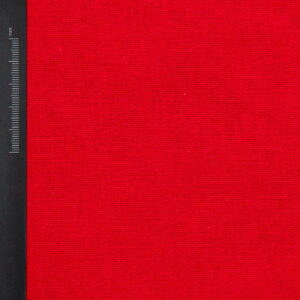

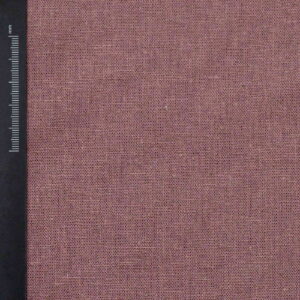

The resultant threads exhibit a remarkable capacity to absorb dyes, ensuring vibrant colors and resistance to fading. Finally, the finished silk threads are wound onto bobbins, cones, or skeins, poised for distribution and adaptable for various textile and sewing applications.

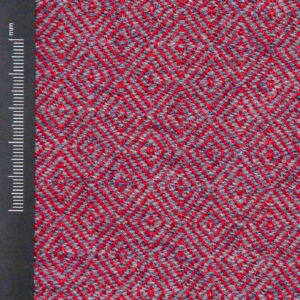

The “26/6” designation in the threads refers to their thickness. What does this mean exactly?

The first number (26 in this case) indicates the thickness of the thread. This number indicates the number of meters per gram of yarn. The higher it is, the thinner the thread is. In this case, it is a thick thread – perfect for sewing, embroidery and even lace-making.

The second number indicates the number of strands twisted together to form a thread. In this case, the “6” means that six individual strands have been twisted together to form the final strand.

So “26/6” means a thick silk thread composed of two single threads, each gram of which is 26 meters of thread.

Silk stands as one of the earliest recognized textile materials, with a history spanning thousands of years. Despite their fragile appearance, silk threads possess remarkable durability, owed to the intricate chemical composition of silk, particularly in proteins like sericin and fibroin.

The strength of silk threads is attributed to fibroin, providing them with exceptional robustness. This component’s capacity to absorb substantial amounts of water imparts flexibility and resistance to decay to the threads. Additionally, silk fibers exhibit resistance to UV radiation, ensuring their strength endures even under intense sunlight.

This distinctive combination of qualities plays a pivotal role in maintaining the vibrant colors of dyed silk threads.

Consequently, silk proves to be an ideal material not only for clothing production but also for diverse applications such as sewing bedding or interior furnishings.

Renowned for their lightness and soft, tactile qualities, silk threads have garnered popularity in the fashion industry. The extraordinary durability of silk enables prolonged use while preserving its original and elegant appearance for years.

The captivating history of silk in Europe traces its origins back to ancient China and unfolds over centuries before attaining prominence in European circles.

Silk held a venerable status as one of China’s oldest and most prized textile materials, with the closely guarded secrets of its production spanning over 2,000 years. China maintained a silk monopoly, exporting it to Europe through the Silk Road, where the revelation of this exquisite material carried severe consequences, including the risk of death. In 550, two daring monks embarked on a perilous mission, allegedly transporting the guarded knowledge to Byzantium. The ruler of Byzantium, Justinian I, sought Chinese silk for its exceptional quality and lucrative profits. Legend tells of the monks concealing silkworm eggs in bamboo sticks, cleverly disguised as ordinary walking sticks, though historical accounts challenge this narrative.

Some sources suggest that Byzantium might have been involved in silkworm breeding earlier, with evidence of silk production in Syria in the 5th century AD and even in Greece in the 4th century BC, casting doubt on the classical monk-driven tale.

Despite uncertainties surrounding the mode of transportation, Byzantine silk production flourished rapidly. The secrets of silk production disseminated widely, leading to textiles adorned with intricate patterns, ranging from religious scenes to fantastical creatures. The imperial court actively supported the industry by commissioning exclusive designs, contributing to the creation of unique silk fabrics.

Byzantine silks garnered immense popularity in early medieval Europe, valued not only for their beauty but also for their high price. Only the wealthiest could afford to possess these opulent fabrics.

In this manner, silk not only endured the arduous journey to Europe but also evolved into a symbol of luxury and elegance, capturing the hearts of elites and consumers across the continent.