Silk threads are created through a meticulous process that uses natural sources from silkworms, usually mulberry silkworms (Bombyx mori).

Silk threads are created through a meticulous process that uses natural sources from silkworms, usually mulberry silkworms (Bombyx mori).

- A process that begins with the collection of silkworm cocoons. Each cocoon unfolds using a spread that can be up to 1,500 meters long.

- The collected cocoons are then boiled or steamed to soften the sericin, a protein that binds the silk fibers together. This softening process makes it easier to unwind the silk threads.

- Once softened, the softened cocoons are unwound. This is often done using a device called a “reeling machine.” As the cocoons are unraveled, the long silk filaments are wound onto spools.

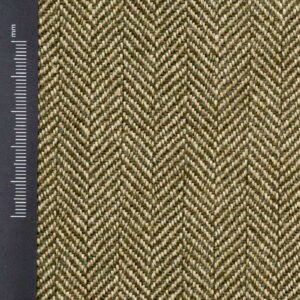

- The unwound silk fibers are then twisted into threads of incredible durability.

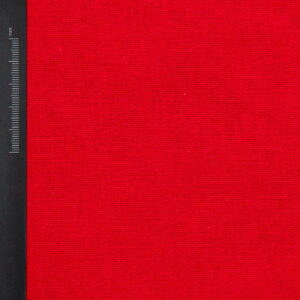

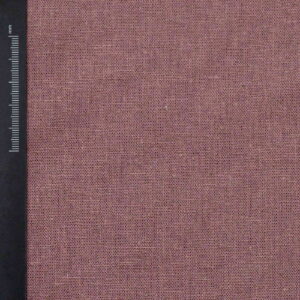

- The finished thread is easy to dye. Silk absorbs dyes well and is resistant to fading.

- The finished silk threads are wound onto bobbins, cones or skeins and are ready for distribution and use in a variety of textile and sewing applications.

The “60/2” marking in the threads refers to their thickness. What exactly does it mean?

The first number (60 in this case) indicates the thickness of the thread. This number indicates the number of meters per gram of yarn. The higher it is, the thinner the thread is. In this case, it means a medium-thick thread – perfect for sewing, embroidery and even lace-making.

The second number indicates the number of strands twisted together to form the thread. In this case, “2” means that two single strands are twisted together to form the final strand.

So “60/2” means a medium-thick silk thread made of two single threads, each gram of which is 60 meters of thread.

Silk is one of the oldest textile materials known to mankind, and its history dates back thousands of years. Despite their delicate appearance, silk threads are extremely durable. But how is this possible?

The secret lies in the chemical structure of silk. It consists mainly of protein, especially sericin and fibroin.

Fibroin gives silk threads exceptional strength. It has the ability to absorb large amounts of water, which makes silk threads flexible and resistant to rotting.

Additionally, silk fibers are known for their resistance to UV radiation, which means that they do not lose their strength even when exposed to intense sunlight.

Thanks to this, dyed silk threads do not lose their color.

This makes silk an ideal material not only for the production of clothes, but also for various applications, such as sewing bedding or home furnishings.

Silk threads are also lightweight and gentle on the skin, making them a popular choice in the fashion industry. However, their exceptional durability means that they can be used for many years while maintaining their original, elegant appearance.

Silk had a long journey from China to Europe, and the secret of its production was closely guarded by the Chinese for 2,000 years. China had a monopoly on silk, which was exported to Europe via the Silk Road. Revealing the secret of its production was punishable by death.

In 550 AD, two monks smuggled this secret to Byzantium, whose ruler Justinian I wanted Chinese silk, or rather the profits from its sale. The legend says that monks brought silkworm eggs from China, hiding them in bamboo sticks that served as walking sticks.

However, historical sources question this story, suggesting that silkworm breeding was already practiced in Byzantium earlier, as some sources indicate the possibility of silk production in Syria in the 5th century AD and even in the 4th century BC. in Greece.

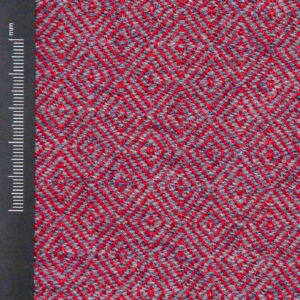

Byzantine silk production was extensive, its secrets were mastered very quickly, and textiles with rich patterns were created by perfecting methods, from religious scenes to fantasy creatures. The imperial court supported this industry by ordering exclusive designs.

Byzantine silks were very desirable in Europe in the early Middle Ages, appreciated, but also expensive. Therefore, only the richest individuals could afford them.